James Baldwin: “White is a metaphor for power.”

#VisionZeroApartheid

What is Vision Zero Apartheid? It is when we mix Vision Zero and policing within a racist society.

A system of white supremacy re-purposes Vision Zero to calm white fears of non-white bodies by using enforcement to impose punitive forms of racial control under the guise of public safety. We then see how public safety itself becomes an essential part of systematic segregation and discrimination in the street. A system of white supremacy reshapes Vision Zero through policing into a racialized and class-based weapon where public safety becomes constructed as for rich white people from poor people of color. #VisionZeroApartheid

Illustrating the segregation of safety through policing, Manuel, Latino delivery worker, wanted to share in his words “this important message to the police”:

In this life we are all human beings, and sometimes I have felt that [the police] have discriminated me based on my color and for being Hispanic… They sometimes stop me and don’t stop others, which makes me feel bad… I know that sometimes I have asked for their help and they don’t give me attention. There are some instances that I have seen [people] rob delivery food from my friends or have robbed them [of money], and [the police] have not cared. I have noticed that when people with white skin or people who are residents or citizens ask for the help of police, the police act. And with us they don’t do that and I’m aware that I’m in a stranger’s country, but that shouldn’t make me less or make them more than they are.

I use the word Apartheid not to equate the atrocities of South African apartheid as the same as the oppression that NYC delivery cyclists experience, but as a way to describe how systems of discrimination and segregation flourish and evolve within racial capitalism, and that these systems are simultaneously transnational and local. NYC Vision Zero is transnational because Vision Zero is an imported policy that originated in Sweden. NYC Vision Zero is local in how we mold its policies, strategies, and implementation to fit the American and NYC contexts of systematic racism that uses policing as a tool for social and racial control.

Vision Zero Apartheid describes a situation now in NYC where: 1) NYC electric bicycle (ebike) riders do not cause many injuries, yet, 2) the City & NYPD have been using Vision Zero to police mostly immigrant delivery workers. Thus far in 2017, in response to white fears about “dangerous” ebikes, the NYPD has already confiscated 923 electric bikes (ebikes) from immigrant delivery workers and ticketed them with nearly 1800 ebike criminal court summonses. Since this is a criminal court summons, if the immigrant worker doesn’t show up in criminal court, an arrest warrant is issued for them.

Financially, since the most common ebike in delivery costs about $1400 new, the NYPD has in effect in 2017 thus far seized over a million dollars in property from low-wage immigrant workers. Furthermore, since the fine for each ebike summons is a staggering $500-$1000, NYC has in 2017 thus far penalized immigrant workers for about another million dollars in ebike fines. This is an example of how Vision Zero Apartheid is brutal in dispossessing marginalized peoples who are excluded from the boundaries of safety that are defined by a system of white supremacy. And we’ll also see that Vision Zero Apartheid inflicts systematic physical and emotional violence.

To discuss Vision Zero Apartheid, I am splitting up this topic into three blog posts:

- Part 1: White Fear, Echo Chambers & Immigrants (this post): This how Vision Zero Apartheid controls public dialogues and processes about safety to only hear the privileged voices in echo chambers while silencing, ignoring, gaslighting, and neglecting voices from marginalized groups like immigrant delivery workers.

- Part 2: “Reining Them In” Policing (here): How Vision Zero Apartheid manifests in policing that is part and parcel about social and racial control for the benefit of white supremacy.

- Part 3: Intersectional Listening (Soon too!): How listening through an intersectional approach transgresses the defined boundaries of white supremacy, which allows us to take collective responsibility and to approach wholeness and liberation.

Borrowing a page from Tamika Butler, my disclaimer is that I will be talking explicitly about race and class among many things. For many of us, talking about race and class makes us feel highly discomforted. I myself feel uncomfortable. I have to resist the automatic urge to run from this discomfort because always being comfortable means that we don’t have to change anything, which makes it easy for us to participate and be complicit in systems of oppression. Comfort is the status quo, an equilibrium. Discomfort is dynamic and messy. Discomfort is where the lived experience of oppression is located, but it is also where the struggle for collective liberation lives.

Echo Chambers of White Supremacy

Howard Yaruss kept exclaiming over and over, “We have to rein these guys in!” These guys meant NYC food delivery cyclists. My head ached from our combative 45 minute phone call.

After we at the Biking Public Project published our maps and results about NYC policing of working cyclists, a couple bike activists approached me about presenting our research to Community Board 7 of the Upper West Side, an area with very high levels of policing working cyclists. The activists thought they could get me on the agenda to expand the public dialogue about delivery workers beyond simple demonization. So after some time trying to get me on the CB7 Transportation Committee agenda, I got told that I should call Howard Yaruss because he had “concerns” about what I would say. At that time in February 2017, Howard was the co-chair of the CB7 Transportation Committee. Because he is also on the Board of Directors for Transportation Alternatives and an avid cyclist himself, the bike activists thought we would have the opportunity to engage CB7 about our work with immigrant delivery workers.

So I called Howard and once we started talking, I knew within a couple of minutes that I would not be allowed to present our work to CB7’s Transportation Committee. From the start, Howard had no interest in what I had to say and I could barely get out a sentence as he constantly and hostilely interrupted me, which made it excruciatingly difficult for us to have a dialogue.

I tried to talk about how we had heard from delivery workers about how working conditions, immigration experiences, customer demands, and policing affected the travel of delivery workers. Howard kept loudly cutting me off by saying that I wasn’t answering his questions, that my arguments didn’t make any sense, and that I wasn’t saying anything that was relevant to the Transportation Committee.

I asked Howard how many delivery cyclists were able to discuss their experiences with his committee? Or at least folks like us (not ideal I know) who work hard to listen to delivery workers about their experiences and needs? He replied none. Even though his committee has a voice in recommending police enforcement in transportation, Howard kept telling me in a patronizing voice, “Your work is nice and interesting, but it’s just not relevant for us.” He told me that I was the one who asked for access to present so I better be able to convince him.

For Howard, it was a complete non-starter when I strongly disagreed with his opinion that delivery cyclists needed “to be reined in” and policed as much as necessary until they “behaved.” At one point he told me that I would be “welcome” to come back later to him if I were to reframe our stance to meet their needs. I am reminded of Adonia’s essay raising concern about the racial blind spots of Vision Zero enforcement and what it’s like to be tokenized:

This is what it is to be a woman of color in this world: you’re in demand based on what boxes you can check, but when your expert recommendations go against the grain, you can be dismissed as a nuisance. They want my exotic face but not the brain shaped by living in this skin.

Feeling tokenized, I asked Howard how they as a “Community” Board could make decisions about delivery workers without ever including them in dialogue? I asked him what he was so afraid about? He didn’t respond to either question. It seemed the immigrant delivery workers were not included in what he considered as part of their community.

This highlights some of the ways a covert system of white supremacy functions by:

- Narrowly defining borders of what is “relevant,” which rigs the debate.

- Constructing an echo chamber with strong gatekeeping to ensure a white narrative by excluding non-white counter-narratives.

- Within the echo chamber, crafting a demonizing and powerful narrative about marginalized communities, which is amplified in white controlled English-language media. In this case, it’s worsened by targeting immigrants who often lack English fluency.

- Making decisions about marginalized communities without their consent or participation.

Last year, the Biking Public Project conducted a media analysis of news stories about NYC food delivery cyclists and we found that 73% of stories about food delivery cyclists did not have a single quote from a delivery cyclist. Thus echo chambers of white supremacy result in a public and dominant narrative that narrowly defines immigrant delivery workers as partial human beings stripped of context and history. For example, racist narratives reduce immigrant delivery workers into uni-dimensional caricatures of irredeemable and dangerous predators who “prowl residential neighborhoods at night. You’ll never see the one that gets you.”

It is impossible to have justice within the terms and borders set forth by a system of white supremacy. A racist system doesn’t want to talk about how working conditions affect the mobility of immigrant delivery workers, because working conditions add context and humanity to the workers and deeply implicates all of us as participating in the production of delivery. A racist system would rather just focus on immigrant “criminality.”

These echo chambers of white supremacy foster many wild fantasies and fears because these echo chambers are isolated. The combination of fantasies and whiteness has enormous power and consequences as Jared Sexton, UC Berkeley scholar, cautions, “You should understand white people’s fantasies because tomorrow those fantasies will be legislation.”

This past week, we saw in action the light speed at which white fantasies transform into law. A white echo chamber of a WNYC (an NPR station) radio story in July complaining about “reckless” immigrant delivery e-bike riders galvanized Mayor De Blasio into action and to announce a sweeping new regime of e-bike enforcement and total crackdown in the name of Vision Zero. This decision that substantially harms immigrant delivery workers lacked any sort of meaningful dialogue with immigrant delivery workers.

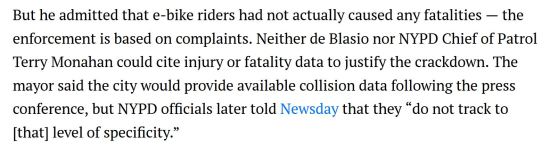

This public demonization of “dangerous” delivery ebike-riders and spectacle of discipline is at odds with the evidence of harm as the city couldn’t provide numbers on injuries caused by ebike riders as David Meyer at Streetsblog notes:

When the echo chamber of white supremacy has defined a group of people as potentially “dangerous,” it doesn’t really matter if immigrant delivery workers have done anything actually harmful to an alarming extent. Being seen by white supremacy as potentially dangerous is cause enough.

Furthermore, likely in an effort to defend against claims of attacking immigrants, the Mayor argued that the ebikes crackdown is about shifting enforcement onto the restaurants and employers, rather than the workers when he says, “The employers purchase the bikes, hire the workers to drive the bikes… So, we have to go after the businesses.” Based on this premise, the Mayor and NYPD outlined a new plan to be able to issue summonses to the restaurants.

However, it is a complete fiction that the businesses own the ebikes. Instead it is the workers who own and use their own ebikes for delivery work. This has been the case for every single one of 100+ delivery workers we have heard from. We have heard about a few employers that do own and provide the ebikes, but this is the exception, not the rule. This fictional premise for a whole new city policy of enforcement is predicated upon a white fantasy dreamed up in an echo chamber. It is a white fantasy that assuages guilt over stealing immigrant property by fictionalizing a world where the businesses are the ones they are taking the ebikes from instead.

When the mayor talks about shifting the enforcement burden away from immigrant workers, it sounds nice, yet what the Mayor described doesn’t actually do this. During the ebike seizure, the delivery worker will still get the same $500-$1000 summons as before. To compare, when the restaurant gets the ticket, the employer summons is only $100-$200, which is far less than the delivery worker who is supposedly “not being targeted” any longer. The Mayor is abusing language, which is work on the behalf of Vision Zero Apartheid.

Another problem with the Mayor’s new plan is that of the independent contractor. NYPD Chief Monaghan stated, “If you’re an independent contractor, same rules and regulations right now. Bike is going to be seized, you’re going to be issued a summons, you’re going to have to pay that summons to get the bike back.” Nearly every delivery worker we have spoken with is unlawfully treated as an independent contractor by the restaurant or employer. The white fantasy here is that delivery workers are employed as W-2 employees (which they should be but aren’t). If the employers hire the workers as independent contractors, this appears to mean that the delivery workers will still bear the enforcement, not the restaurant. These fictions make sense in the white echo chamber, but don’t line up with the workers’ reality.

In addition, both the WNYC radio segment and De Blasio’s remarks worked hard to “other” the immigrant delivery workers by depicting the e-bikes they use as “not bikes” but rather as dangerous “motorized vehicles.” This seeks to exclude ebike riders from the cycling movement. When the Mayor talks about protecting the elderly from “reckless” delivery ebike riders, he is excluding the many elderly immigrant delivery workers in their 50s and 60s who rely on ebikes to do delivery work safely. Elderly immigrant workers need safety too (h/t Macartney). When a reporter asked the Mayor about the needs of older immigrant delivery workers who need ebikes, part of De Blasio’s response was, “If someone couldn’t make those deliveries anymore, my hope would be that they can find some other type of work with that restaurant or that business, but I have to put public safety first, that’s the bottom line.” For many of the immigrant delivery workers we have spoken with, other job options tend to be scarce with even less pay and worse working conditions. When De Blasio says putting public safety first above, it’s clear he is excluding immigrant delivery workers to coddle white fears.

This “othering” strategy works disconnect the highly privileged residents who order endless amounts of food from what happens in delivery even those these residents are implicated and responsible too. It’s as if they forget why delivery workers are present and in a rush when residents say things like, “They’re out all hours of the day and night, and they don’t abide by any of the rules. They’re so reckless.”

An ebikes crackdown exposes the immigrant workers to more policing, which also makes them more vulnerable to ICE and deportation even if they have a green card. De Blasio talks a big game about being a progressive “Sanctuary” City for immigrants, but these city policies on ebikes enforcement make NYC less safe for immigrants.

This mirrors what Sahra Sulaiman wrote about the oppression that occurs when a progressive community fails to see and examine its own biases and participation in oppressive systems:

Even with all that, I can honestly say I was genuinely not prepared to watch progressive people of privilege – including so many that claim to care about equity, justice, and inclusion – spend a week excusing away participation in “n*gger” chat rooms, engaging in lengthy and heated debates about whether putting the n-word in quotes made it more or less racist, proclaiming themselves to be oppressed minorities in need of bike lanes, pronouncing unsavory online habits as mistakes we all make, and being actively indifferent to any harm that might have been caused to those targeted by transphobic, fat-shaming, misogynist, racist bottom-feeders…

And the fact that [marginalized] groups are silenced or tokenized or bullied every time they try to challenge the existing narratives and biases that uphold that landscape is not “healthy” – it is seriously fucked up.

It also happens in how the bike movement co-opted the hit-and-run death of Gelacio Reyes with a tearful ghost bike installation and ceremony that I attended. I started hearing secondhand that Gelacio was riding an ebike when the driver killed him, but I didn’t see any mention of it in the news coverage, bike advocacy, or at the ghost bike ceremony. Some weeks later, we happened to be able to talk with Flor, Gelacio’s wife, and amid our conversation, she mentioned that Gelacio was riding an ebike. Flor told us that Gelacio had to borrow money to buy an ebike in order to be able to get hired by a restaurant to do delivery work.

It is absolutely disturbing to see how many cyclists used Gelacio’s death to argue for more protected bike infrastructure, while at the same time, numerous cyclists continue to deride the delivery workers using ebikes as monstrous dangers. As if bicyclists and e-bicyclists don’t bleed the same as they share the same vulnerabilities to car violence. As if we have to hide the fact that Gelacio was riding an ebike so that he would deserve a ghost bike. The bike and safe streets movements writ large need to stop doing work on behalf of oppressive systems.

If it helps to understand the problem I am talking about in “bike” terms, one the major complaints from cycling advocates is that when a driver in a motor vehicle strikes and kills a cyclist (or pedestrian), the NYPD’s default mode is to victim blame. This happens partly because of a cultural bias towards cars, but also in the wake of the crash, only the driver is alive to testify and the cyclist (or pedestrian) can’t speak because they are dead. The NYPD often just accepts the word of the driver who defines the cyclist (or pedestrian) at fault, which the NYPD repeats to the media so that this single-sided story gets amplified and taken as truth. Similarly, in regards to ebikes, it’s as if we are treating the immigrant workers as dead and unable to speak for themselves.

Many in liberal northern cities like NYC imagine that white supremacy lives far far away, like what happened in a southern place like Charlottesville. But systems of white supremacy are deeply embedded in liberal “sanctuary” cities like NYC. There’s a reason why “progressive” NYC still has the most segregated schools in the country. NYC was ground zero for racist broken windows policing. We can’t just only say we are anti-racist and that we are a sanctuary for immigrants, we actually have practice what we preach. It is often unexamined bias and unwillingness to actually practice anti-racism that makes Vision Zero Apartheid possible.

When We Connect Working Conditions to Delivery Cyclist Travel

What happens when we listen to the stories of immigrant delivery workers? We can cross the boundaries set by white supremacy, which allows us to understand how our society has constructed an unjust reality for delivery workers in service of white supremacy. We expand our field of view to see immigrant delivery workers in greater complexity and wholeness and how we all are implicated in what happens in delivery. We can begin to undo Vision Zero Apartheid.

Stealing from Workers

Map of the Upper West Side where workers have reported wage theft and other violations at their restaurants to NMASS.

While at the offices of the National Mobilization Against Sweatshops (NMASS), I saw the map of the Upper West Side of NYC to the left. NMASS explained to me that the sticky notes are all the restaurants where restaurant workers have informed NMASS of wage theft and other workplace abuses. The maps shows that worker exploitation is rampant and as NMASS explained, this was not a systematic survey of restaurant workers, so the problem is actually far worse and all around us.

The Economic Policy Institute estimates about one billion dollars of wage theft every year in the state of New York. When NYC immigrant restaurant workers summon the courage to organize, they have successfully sued for stolen wages in winning some staggering sums – $1.3 million, $4.6 million, $700K, etc. But often what happens is that the restaurant owners shift and hide assets, close and reopen the business under another name, and use other tactics to avoid paying workers their stolen money.

Wage theft is robbery, yet it is usually treated as a civil matter rather than a criminal matter. This says a lot about how crime is defined by power. I find it hard to imagine a scenario in which there wouldn’t be hell to pay if muggers and robbers went around the Upper West Side to steal multiple millions of dollars from residents on the street and from homes. Yet there is this kind of rampant theft, but it’s the powerful stealing from workers.

In this pervasive system of wage theft, many restaurants pay immigrant delivery workers $20-40 plus tips for a 12-16 hour work day, which amounts to $2-4/hr before tips. This severe form of wage theft exerts extraordinary pressure on the workers to make up wages through tips. Tipping is rooted in racist history and social control. And the workers quickly discover that they make make more tips by speeding up to do more deliveries especially if they use an ebike. Speeding up and using an ebike is one of the very few significant things that delivery workers have control over in their working conditions. Yet this one point of agency and control by immigrant workers is seen as an intolerable threat by rich white people. Essentially, it’s highly privileged people saying that the immigrant workers do not have the right to participate in shaping the city for their own needs.

Unsurprisingly, workers get directives from the restaurants to go faster and do more deliveries for greater profit. Many customers use tipping to demand faster deliveries and thus delivery workers know that customers may withhold tips if workers take too long. Homer Logistics told me that customers don’t give tips to their delivery workers on 20% of deliveries.

Manuel, a Latino delivery cyclist, describes the lack of customer understanding of the delivery context and its challenges:

[Customers] think we don’t arrive quickly enough for the delivery, and they get angry and take the food and don’t give us tips. Sometimes they are annoyed by us if the food arrives cold and get angry even if it is not even our fault. Sometimes there is so much traffic, sometimes the restaurant is busy, and even though we tried our best to get everything done as fast as we can, it is not possible and that is the part that people don’t understand. We understand they are hungry, but it is not our fault. There is traffic. Sometimes the police stop us and they don’t know we are trying to get food delivery as quickly as possible. That’s the point that people don’t understand, they are irritated by us. And another part besides treating us badly, they don’t tip us and sometimes they end off by saying bad words to us. And because we do not want to lose our jobs, we don’t say anything back. They [call us] idiot, crazy, stupid.

I asked Carlos Rodriguez Herrera, an organizer with NMASS and a food delivery cyclist himself, about the pressures of wage theft and tipping and he commented that if delivery workers were paid fair wages and benefits, that yes, they wouldn’t have to go so fast.

In addition, when cars hit delivery cyclists and cause injuries, the delivery workers almost never receive workers compensation from their employer. The employers, whether restaurants or 3rd-party apps like UberEats, Seamless, or Doordash, typically and unlawfully classify the delivery cyclists as independent contractors, which allows the employers to deny delivery workers benefits like workers compensation or health care. Thus many workers have told us stories of being hit by a car, having a severe injury like a fractured collarbone, and getting up to complete the delivery, because they can’t afford to stop working. While the Mayor and the privileged largely complain about their fears of potential violence by delivery e-bike riders, what delivery workers experience is real systematic violence. #VisionZeroApartheid

Being unlawfully treated as independent contractors means that nearly all delivery workers have to pay at considerable personal cost for all their delivery equipment – bikes, ebikes, maintenance, lights, bell, helmet, reflective vest, cellphone use, etc. When the city designs a new city enforcement policy based on the fantasy that the restaurants own all the ebikes, it’s absolutely clear that they have not cared to listen to workers. When we pay for the delivery, the hidden costs to keep our meals cheap are being paid for by the workers.

There are real dangers of robberies and assaults while out on deliveries as Wong, a Chinese delivery worker, described:

A lot of [delivery workers] get robbed. Deliverymen will be assaulted during the robbery, have our money taken, and also have our legs broken, our teeth broken. Even if we are injured, we still have to keep working. Even if we call the police, the police come very slowly and the police just make a report, and nothing happens… Some attacks actually killed delivery workers. And we feel really helpless because once we have been killed, no one can take care of our families, it’s as if we just vanished. There are no people who can speak up for us.”

Because a lack of trust that police will do anything to help them, many robberies and assaults against immigrant delivery workers go unreported. Does it make us safer when a large group of people are not reporting violent crimes?

With long days, numerous miles (often 20-60+ miles/day), and broken bodies, delivery workers have been grateful for ebikes in making their deliveries more comfortable and faster. Many immigrant delivery workers are in their 50s and 60s and don’t have any other real options for work after many years of delivery work. These delivery workers feel that ebikes make it safer for them.

When rich white people talk about the menace of ebike riders, they are excluding delivery workers from the boundaries of public safety. If Vision Zero is about providing safety in travel, why doesn’t the city use #VisionZero to safeguard delivery workers? Instead, we get #VisionZeroApartheid that addresses white fantasies and fears while reinforcing a system that steals the delivery workers’ wages, bodies, and dignity.

Rich Buildings as Borders

At rich buildings, delivery workers have to negotiate sometimes hostile doormen and security, which one Chinese delivery worker described as like “border patrol.” Building security too often treat delivery workers poorly, delay delivery workers, and/or force delivery workers to go through the back entrance.

Deborah, a biracial female delivery worker, describes a degrading experience in needing a customer to fill out and sign a credit card receipt so that she could get a tip. However, the security guard insisted that delivery workers weren’t allowed upstairs. They argued and finally the security guard took the credit card receipt, called the customer, and put the credit card receipt by itself on the elevator, and sent it up to the customer.

When workers are forced to go through the back entrance, it costs delivery workers a lot of time. Sometimes the back entrance is on a different block. Also taking the solitary freight elevator is much slower and busier than the bank of elevators through the front lobby and because many delivery workers are competing to use the freight elevator. One delivery worker estimates that it just takes a couple of minutes to complete a delivery and exit by using the front elevators as compared to taking about 20 minutes when they are forced to use the freight elevator. Jose, a Latino delivery cyclist describes what taking the back freight elevator feels like:

[Security guards] make us go to the freight elevator because they think we are going to dirty [the place], or something else. It makes us not be able to be efficient in our job and it is a form of discrimination because it makes us feel bad that we can’t go through the regular elevator.

Once, I was shadowing a delivery worker in Midtown and security forced us to go through the back and use the freight elevator to make the delivery. On the way back down, we used a normal elevator taking us to the front lobby. We started moving toward the exit when a security guard screamed at us, “Stop! Go through the back!” We froze as we were already about halfway through the front lobby when another security guard waved us through with irritation and said, “Oh, just go through!”

Another cost of time is when the worker is not allowed to go up to make the delivery directly and must wait for the customer to come down. During my shadowing of a worker, we once waited for a customer for 25 minutes before she showed up.

Sometimes the customer will tell the delivery worker to leave the food with the doormen or messenger center at the back entrance, which some workers think makes it easier for customers to skip tipping on credit card orders because the customers never actually have to stand face-to-face with the worker.

A delivery worker dropping off a food order in the back of the building in the messenger center. He never sees the customer.

These stories demonstrate that #VisionZeroApartheid becomes enacted spatially and in practice in many rich buildings. Delivery workers are often treated as a threat or like a contagion that needs careful social control with minimal contact with highly privileged customers. These social controls needlessly cost delivery workers human dignity and invaluable time within tip-based work.

If we care about “public safety,” we need to include the marginalized like immigrant delivery cyclists within the boundaries of the public that we are safeguarding otherwise we are being moral monsters. This means addressing a system of exploitative working conditions. This means that we should rethink our spaces, both streets and buildings. It means having the immigrant workers tell their stories and to define their own experiences.

The way we treat delivery workers is incredibly dehumanizing as explained by Michael, a Black Hispanic delivery cyclist, “I feel like some people, if there was slavery, they’d just buy a slave. That’s what I feel like sometimes, just the way [customers] treat people.” #VisionZeroApartheid

The Vision Zero Coalition of San Francisco acknowledged that VZ could be used to racist, anti-immigrant ends back in February when Trump was first pushing his deportation agenda. Below is the statement the group released:

Statement from Vision Zero Coalition:

We Renounce Deportation Based on Traffic Violations

San Francisco, Calif –– The undersigned members of the Vision Zero Coalition release the following statement in response to the Trump Administration’s announcement on February 21 that a forthcoming executive order may expand deportable offenses to include traffic violations.

Advocates for safe streets are tired of hearing the trivialization of traffic violence as “just a traffic violation” or “no more important than a speeding ticket.” Traffic violations can lead to death and serious injury, especially for vulnerable users of our streets. People walking and biking are frequently the victims of such injuries, and seniors, children, and people with disabilities are disproportionately at risk.

However, as members of the Vision Zero Coalition, we forcefully reject the Trump administration’s plan to pursue deportation for undocumented immigrants who have committed minor traffic offenses. Individuals in low-income communities and communities of color are disproportionately killed and injured by traffic violence on our streets. Now, the primary victims of this violence may also be unfairly targeted by biased and punitive enforcement.

We refuse to allow Vision Zero — San Francisco’s goal to eliminate all serious and fatal traffic injuries by 2024 — to be perverted into an excuse to round up and deport our undocumented neighbors and friends, just as we have previously denounced racial profiling committed in the name of traffic safety.

The undersigned seek to work with, not against, the very communities now under attack by the xenophobic and racist policies of the Federal government. We declare unequivocally that Vision Zero must not be used as a cover for raids, racial profiling, or other unjust attacks on our fellow San Franciscans.

this is masterful work Dosik. Get that PhD done and get cracking on forcing real change with your advocacy!